My toothbrush is fucking electric

The world is a great place to live, and 2024 is a great year to live in it

This morning was boring. I got up, put on clothes, didn’t make my bed, and went to the bathroom. As I brushed my teeth, I stared out of the hole in the wall of the indoor-outdoor concept design of the 6th-story bathroom at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Despite the walllessness, all I could hear at 8:30 AM was the sound of Chai Chee Foon mopping the floors and the buzz of my electric toothbrush.

My parents have long insisted I use an electric toothbrush and for some reason, this moment was the first I ever questioned it—Does an electric toothbrush really make a difference? I hit the books (my laptop). Luckily for Phillips' stock price (I own none), it does. Thanks, Ken and Cheryl.

It is remarkable to me that I own such an object. For my electric toothbrush to turn on this morning, humanity had to understand electricity, generate it at scale, put it into wires, change the voltage a few times, figure out batteries and outlets, and make all that not catch on fire. Not to mention invent the toothbrush. I use my electric toothbrush twice a day, and I didn’t have to invent any of that.

To me, that’s amazing. On this front, I think my generation has lost the plot a little bit. Sorry if that’s rude to the 2 billion Gens with whom I share a Z, but the ever-common pessimistic assumption that we live in a uniquely horrid and hopeless society is… wack. And objectively incorrect. Young people are doing a great disservice to ourselves, our elders, and most importantly, our future, by failing to realize how amazing the world is today.

Try complaining to Alexander the Great

Like with my toothbrush, I recently came to wonder: Why is Alexander so great? Turns out it happened the same way it has for all legendary men: he took a lot of land.

Not to say that’s not impressive–you try conquering the Persian empire. Bet you can’t.

After all this, he died at 32 from typhoid. Son of a King, ruler of an Empire, and one the wealthiest people of the age, yet nothing could have prevented inevitable death once he had contracted the disease.

This may be unsurprising—everyone agrees that life was shorter and harder in 323 BC.

Here’s the crazy thing: If Alexander the Great had been born in 1900, his life expectancy would have been the exact same. That is, in 1900, the average life expectancy of a newborn was 32 years.

2,247 years after Alex’s passing, in 1924, the son of U.S. President Calvin Coolidge (who? anyway…) was playing tennis shoeless on the White House grounds when a blister formed on his toe. He soon felt feverish and was dead within a week. Again, one of the most powerful men in the world, yet he could not save his son from a blister. This time, only 100 years ago.

The average life expectancy has more than doubled since 1900 to 73.4 years today. People still die of diseases such as typhoid and Staphylococcus aureus infection, but far fewer.

For most of human history, around 1 in 2 newborns died before reaching the age of 15. By 1950, that figure had declined to around one-quarter globally. By 2020, it had fallen to 4%. Far too many children still die of pneumonia, tuberculosis, malaria, and other preventable diseases, but far fewer than ever before.

This is not a miracle. We did not suddenly evolve to be stronger than the mosquito or less hungry. We discovered antibiotics and began sterilizing surgical tools so that more than 50% of patients survived operations. We figured out how to make fertilizer out of thin air (literally), which is responsible for the food supply of around half the modern population. We have clean water systems, preventing cholera from ripping through London as it did in 1854. We have an antibiotic for the Black Death and 88 percent of 1-year-old children in the world today are vaccinated against some disease (that last one shocked me).

If you want to trade generations with your Mom, you were probably born in a wealthy country

There have been several generations separating the fate of Coolidge’s son and modern medicine in wealthy countries. Perhaps if he had taken up tennis four years later, the 16-year-old could have been treated with penicillin. Improvements in lifespan, income, and quality of life have been improving gradually. While wealthy nations have had the privilege of decades of progress, less wealthy countries have seen the most improvement in the last generation.

When my parents were born, life expectancy in Canada was 72.2 years. At the time of my birth, it was 7.2 years higher. A 10% increase in one generation. A win.

If my parents were born in Nigeria that same year, they could have expected to live to 38.5. I would have been projected to live to 50. A 30% increase in one generation. In China, a 32% increase. In India, 34%. A triumph.

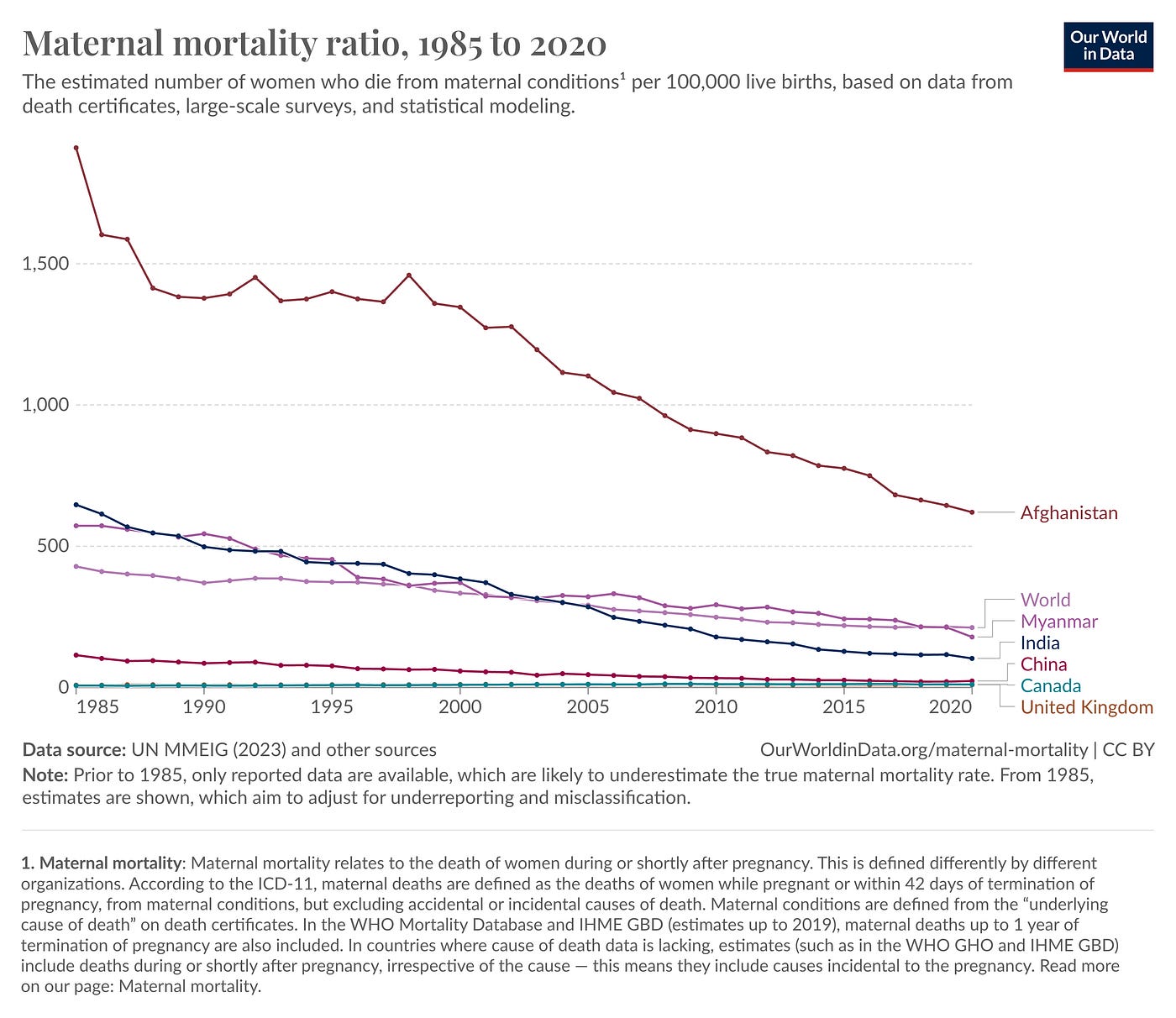

Similarly, it would have been unlikely for my mother to die in childbirth in Canada in 2001. In wealthy countries, maternal mortality has remained low and essentially unchanged from my birth to today.

If my Grandma remained in Myanmar, where she was born, there is a ~1% chance she would have died giving birth to my mom. If I was born in Myanmar, there is a ~0.3% chance my mom would have died. Today, 0.17% of women in Myanmar die in childbirth. Across three generations, the likelihood that a Burmese child never meets their mother dropped to 1/3, then 1/3 of that.

Pick almost any topic, and these optimistic trends continue.

Since 1970, rates of undernourishment in U.N.-defined ‘developing’ countries have dropped from 1 in 3 people to 12%.

In 1900, 21% of the global population was literate. When my mom was born, 55%. Today, 87% of the global population can read and write, unlocking education and infinitely more career opportunities. Again, the largest increases in the last generation have been in less wealthy countries.

In 2000, 2 in 10 people lacked access to electricity; today fewer than 1 in 10 lack access. Most of this change has occurred in low and middle-income economies.

Children in wealthy nations may envy our parents’ generation, free from Zuckerberg’s iron grasp on our attention span, rising oceans, and Logan Paul. But, firstly, we are healthier and wealthier than our parents on average. Second, to pretend that the world of 50 years ago was better than today takes an incredibly Western lens on history. For decades, North Americans and Western Europeans have benefited from development, with functioning healthcare systems, ample food, clean water, heat without having to build a fire, and clothes without having the skin a beaver. Like my parents, mosquito bites remind me more of smores than they do of malaria. The flu reminds me of chicken soup, not the death of a loved one. Toilets are the content of immature jokes, not a luxury.

The world has become leaps and bounds better in the last 50 years*, especially for people in less wealthy nations. And this trend continues.

*There are, of course, many localized exceptions to this. People in many places are suffering more today than they were 50 years ago due to wars, political instability, and other humanitarian crises. However, when we look at humanity as a whole, the trends for quality of life are positive.

Ken was scared too

I know what you’re thinking: But Cassia, you forgot to mention that the world is bad. 33,443 civilians died in armed conflicts in 2023. The ocean is knocking on the doors of the world’s poorest people. Elon Musk bought free speech and gave it a worse name. We’re still arguing about whether nuclear energy is worth our time. Hedge funds apparently profit from catastrophic natural disasters (it’s called disaster capitalism). The doomsday clock is 90 seconds to midnight. Like 1/2 the cast of Glee is dead. I mean, fuck.

Knowing this, it is only natural to be scared. Bo Burnham eloquently phrased the common outlook on humanity: Twenty-thousand years of this, seven more to go.

But perhaps, truth is not the source of fear. Perhaps we’re always scared. According to Hans Rosling, “One week after September 11, 2001, 51 percent of the US public felt worried that a family member would become a victim of terrorism. Fourteen years later, the figure was the same: 51 percent. People are almost as scared today as they were the week after the Twin Towers came down”.

In 2022, 78% of Americans said that crime in the U.S. is increasing. Meanwhile, crime has seen a steady decline.

I once told my dad (the aforementioned Ken) that my generation has to deal with climate anxiety, a type of existential dread with which he could not relate. He looked at me, shocked. His entire childhood they feared a nuclear apocalypse, until and after the Cold War drew to a close in 1991.

In 1968, Paul R. Ehrlich sent the world into a frenzy with his popular book The Population Bomb, incorrectly predicting that population growth would cause worldwide famines. People panicked.

For gosh’s sake, does anyone remember New Years 2012?

Any bad news will generate fear, and today, we get more bad news than ever.

Cheer more for electricity than you complain about its sources

Fear and pessimism are not just plagues on mental health. I believe the rhetoric of a rapidly deteriorating society is dangerous. If we fail to see what has worked so well, we risk neglecting the systems that drive positive change. If we believe that all we have accomplished is negative, we will not upkeep the solutions and processes that are slowly lifting billions out of poverty, educating children, producing enough food for 8 billion, and creating vaccines. Recognizing and upkeeping what has worked is a humanitarian imperative.

Pessimism and anger, it seems, are also often rooted in simplistic explanations of the world. “When we identify the bad guy, we are done thinking. And it’s almost always more complicated than that”, writes Hans Rosling, “This undermines our ability to solve the problem, or prevent it from happening again, because we are stuck with oversimplistic finger pointing, which distracts us from the more complex truth and prevents us from focusing our energy in the right places.”

Most dangerously of all, if the world is fucked, we can sit back and watch it burn. Pessimism is the enemy of hope. If we believe all of human history has led us to our worst point, why would it get better now? This trend of hopelessness is seen in the declining drive to have kids: In the U.S. 47% of people under 50 say they do not want to have children.

Pessimists try to be right. Optimists try to build something better.

I believe there’s room for positivity everywhere. Growing access to electricity doesn’t only power toothbrushes, it allows children to study past dark, enhancing their education. It provides energy to cook, decreasing dangerous indoor pollution from unclean cooking fuels. Electricity makes life better. Three cheers for moving electrons. Instead of using less of it, we’ve created solar panels, which are now the cheapest form of electricity. We can figure out how to make it the most widespread. A triumph.

Slow progress is visible if you study the past, then look around. If it’s optimism you seek, study history.

My boring morning was an immense privilege. I brushed my teeth today because someone other than me figured out oral hygiene, and I only had to thoughtlessly obey my parent’s advice—now my teeth won’t fall out. I can’t tell you how grateful I am for indoor plumbing. Least of all because poo is smelly. More poignantly, because I don’t have to throw my feces out the window onto my neighbour’s head, donating cholera to the village at large.

I am so grateful for the systems that took millennia to create, getting us to the last 100 years, when finally, Alexander the Great could expect to live beyond 32. This is not the worst time in human history. For almost everyone, it is the best. If we continue on this path, looking at the slow progress, I believe it will get better.