Can we fill a pothole without cracking planetary boundaries?

Some information about concrete that you didn't ask for

My Grandma grew up in the small island nation of Malta. You can tell by her tendency to put the emphasis on a strange syllable of a word. Congrats, you can now sniff out a Maltese accent.

While whipping her around the streets of Markham, Ontario in my 2013 Hyundai Elantra, I noticed: We pronounce concrete with an emphasis on the first syllable, except for when we’re using it as an adjective. The road is made of concrete. “Let’s make these plans more concrete”.

Language, amirite?

If you’re wondering if there’s a point, I suggest you read a different piece of content.

That wasn’t interesting, but concrete actually is

Contrary to everyone but that one civil engineer at a frat party, concrete is pretty cool. Concrete is the most widely used substance on the planet, after water. In the time it takes you to read this sentence, the global building industry will have poured more than 19,000 bathtubs of grey sludge.

The concrete jungle has become a symbol of development (leave it to Alicia Keys to tell you it’s where dreams are made of), but a source of environmental destruction. The concrete industry produces 5-8% of the world’s greenhouse gasses, which is more than the entire aviation industry. Excitingly, people are cooking up some creative ways to keep buildings sky-high and carbon in the ground.

In some ways, concrete and carbon dioxide are a perfect match. Injected CO2 can strengthen concrete, and recycled waste products can be mixed into concrete to reduce costs and emissions.

We don’t need to stop building with concrete to mitigate carbon emissions from this sector. We may not even have to increase the cost of construction. Innovation in this business is popping off, and I’m gonna tell you about it (I guess we found the aforementioned point).

BTS of a grey industry

“What is concrete made of?” is the kind of pub trivia question that could ignite a sudden need to use the bathroom–You can’t publically admit you thought it was a mined ore. To protect your quiz night ego, the answer is: around 10-15% cement, 60-75% aggregates (typically sand or gravel) and 15-20% water1. Cement is the traditional precursor to concrete.

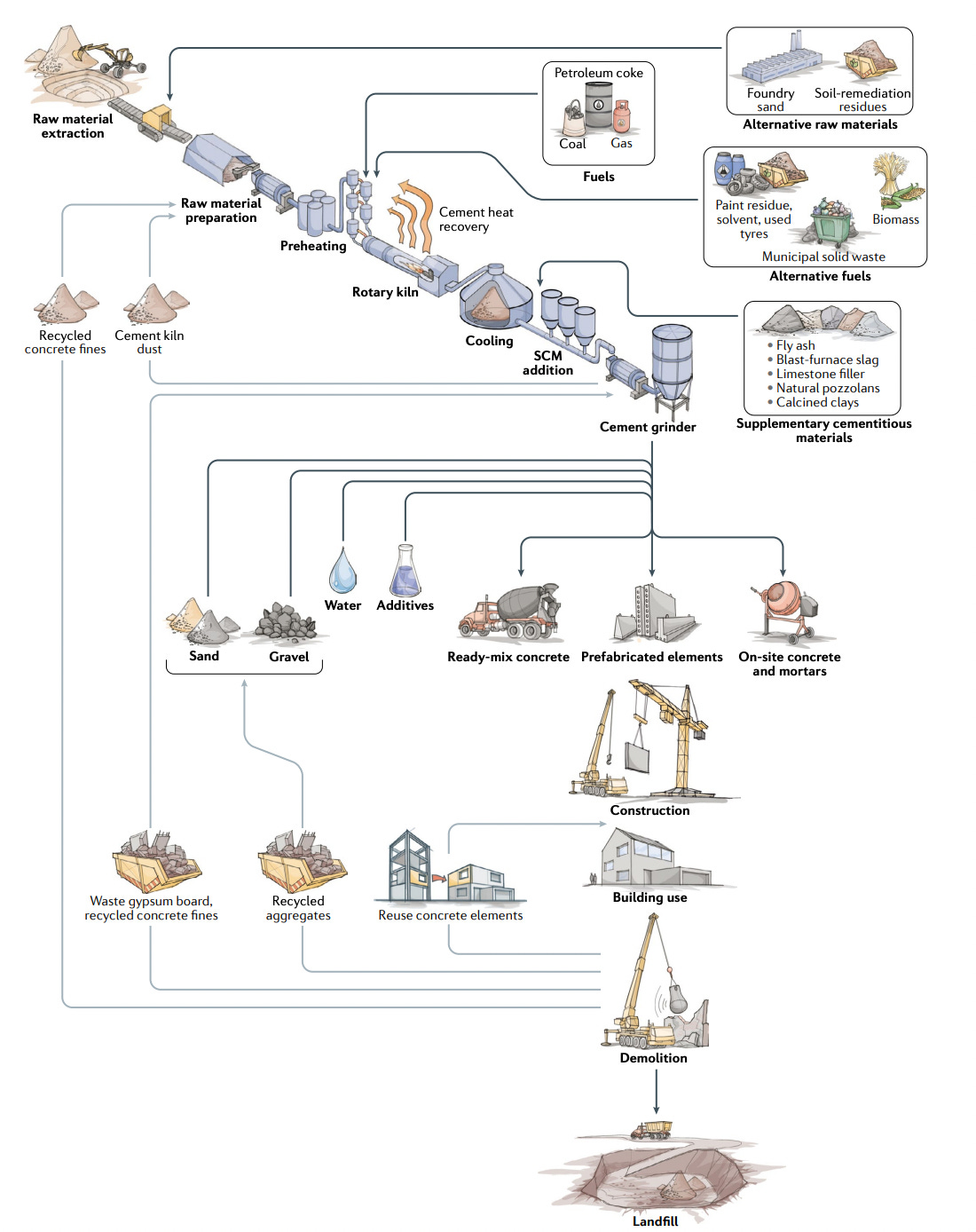

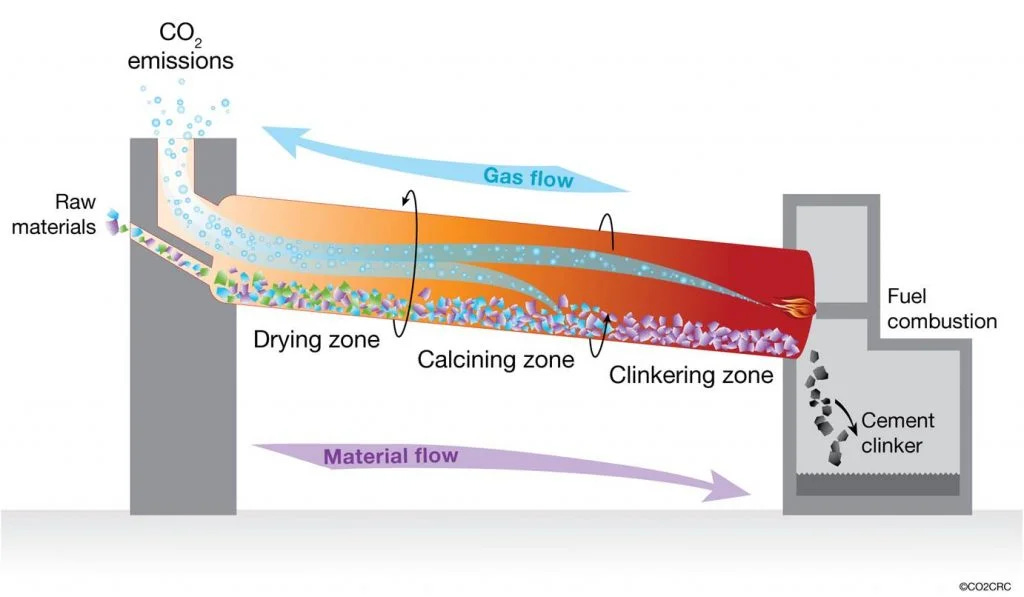

To make cement, limestone, clay/shale and other materials like sand and iron are combined in a massive rotating kiln that operates at ~1500 degrees Celcius. The kiln is tilted so that a new pebble-like substance slowly drips out the bottom. Those pebbles, called clinker, are mixed with more limestone and ground into a very fine powder. That cement is mixed with water and aggregates to make concrete.

Clinker production is the most energy-intensive stage in cement production, accounting for more than 90% of total industry energy use and virtually all the fuel use. In most countries, coal is the preferred energy source for this heat generation.

The simplified chemical equation for cement is as follows:

5CaCO3 + 2SiO2 ➝ (3CaO,SiO2) + (2CaO,SiO2) + 5CO2

CaCO3 is from limestone. SiO2 is from clay/shale. 3CaO,SiO2 and 2CaO,SiO2 are both clinker compounds. CO2 is a byproduct.

For every ton of cement, 0.9 tons of CO2 are produced. It’s a 1:0.9 ratio of product to byproduct.

In summary, we’re burning a few good T-Rexs to heat up some materials whose molecules switch around to make more CO2. Great.

For the BComms

All said and done, the cost of concrete comes to around 30-40% raw materials, 25-35% energy, 10% transportation, and 15-20% labor and other costs2.

There are several large producers trying to cook up an oligopoly on sticky grey muck (e.g. LafargeHolcim, Anhui Conch, CNBM). However, since governments dominate as concrete purchasers, they sometimes try to support small producers as well.

For large projects, builders work with concrete producers to tweak the recipe. Hundreds of factors play into the ideal concrete for a given project: general climate, humidity, earthquake risk, the expected lifespan of the project, etc. After customization, the process looks something like this:

I’m often amazed that buildings never just fall over. No one mismeasured, misordered or forgot a beam or two. Turns out, quite a few people are involved in building stuff, thank the lucky stars. That also means more folks gotta stick their noses in and have their say. Neither demand nor supply of cement is centralized, which makes for a long and disjointed value chain:

Finally, concrete can be poured or stacked or spread. And after all that, good luck slapping down cement in a rainstorm.

Many aspects make disrupting this industry hard: The slew of parties involved in each order, minimal communication between such parties, fluctuating energy prices, sticky bureaucratic government buyers, regulations, specific expected qualities (such as a 90-minute liquid lifetime), and fragmented policy.

Nevertheless, we’re still trying. Bless the optimists (of which I’m one).

Decarbonizing cement

Coming in hot at 8% of global GHG emissions, decarbonizing this sector could have a substantial impact. How can it be done?

Playing matchmaker

Given their chemistry, cement and CO2 need to go on a date. There are currently a few matchmaking services on the market.

Cement-free concrete can be made with carbon curing. Captured CO2 can be injected into traditional concrete, as CarbonCure does3. Once CO2 is converted to mineral form, it never reenters the atmosphere, even after the concrete is demolished.

Cement can also be replaced with steel slag and infused with CO2. Pre-cast concrete can be made with the usual equipment, then put into a carbonization chamber where CO2 reacts with the slag to create calcium carbonates, finishing and strengthening the concrete. Pretty swaggy. One company doing this is CarbiCrete (🇨🇦💪).

Buzz buzz ⚡️

Leave it to electrochemists to find a way to use electricity, rather than heat, to break feedstock into calcium and silicates. Sublime Systems is a company using non-limestone materials to generate the precursors to cement.

Catching carbon (CCUS)

Alternatively, the process could remain virtually unchanged while the CO2 is captured. Leilac has developed a system to directly capture the CO2 from kilns.

Stop wasting stuff (circularity)

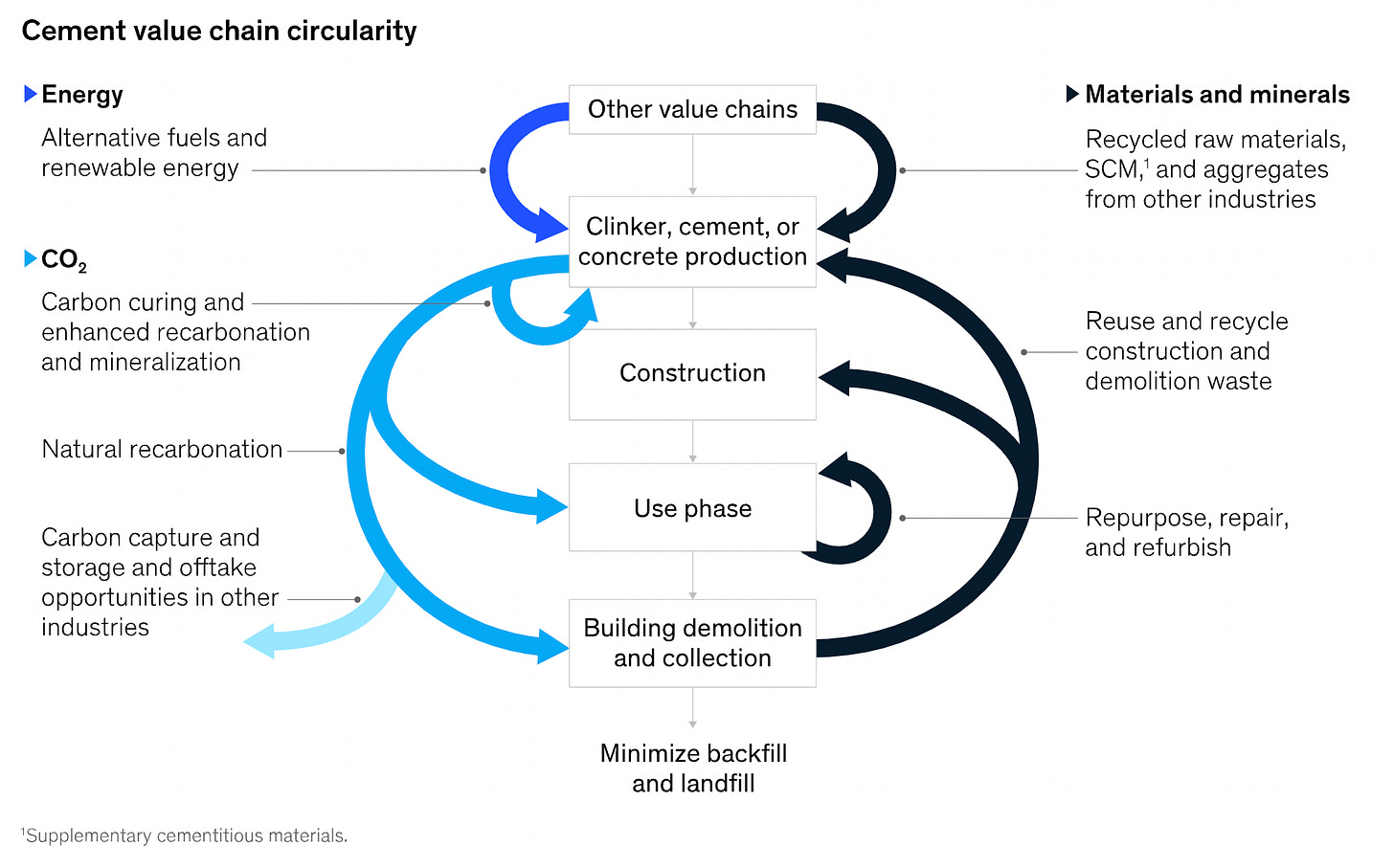

While mineralization, carbon curing, and CCUS have significant CO2 abatement potential, these solutions will almost certainly rely on carbon pricing to achieve cost competitiveness. Meanwhile, partial replacement of clinker with construction and demolition waste (CDW) could save up to USD 60 per metric ton4. This is largely because the cost of landfill from CDW can exceed USD 100 per metric ton. The value of CDW reuse is estimated at USD 24 billion by 2050.

It is estimated that roughly 2.6 billion metric tons of CO2 emissions could be avoided or mitigated by applying circular solutions for cement and concrete by 2050. That’s equivalent to 6.25% of 2024’s global emissions. Alternatively, Kylie Jenner could take her 17-minute flight 2 billion times. Busy girl.

According to McKinsey & Company, “The cement value chain is well positioned to create closed loops, or automatically regulated systems, for carbon dioxide, materials and minerals, and energy”:

Recycled materials have successfully gained traction. In Nordic countries, cement from demolished buildings is being reused in structures. It is now commonplace to find geopolymer concrete, in which around 30% of the cement is substituted with industrial by-products such as ground granulated blast-furnace slag (a byproduct of iron production) and pulverized fuel ash, also known as fly ash (a byproduct from coal powerplants). Ironically, the availability of these materials relies on the continuation of traditional steel production and fossil fuel energy. But for now, we have plenty.

Critical barriers still exist in the concrete circular economy. It is currently inefficient to sort used concrete from wood, metal, and glass. Concrete made with recycled materials is often significantly weaker. Occasionally, contaminants can be flagged in quality control checks, forcing producers to discard a batch. All problematic, but not insurmountable. AMP Robotics, for example, is automating demolition waste sorting.

I am a fan of producing what we need with minimal excess. Theoretically, this is an equation for economic and environmental efficiency. For this reason, I’m bullish on concrete recycling, the replacement of cement with ground CDW, and the integration of waste products from other industries into this supply chain.

Building a new NYC every month

Looking ahead, the global demand for new infrastructure is projected to require the material resources equivalent to constructing an entire New York City every single month. I guess Alicia Keys produced some strong propaganda. From an environmental perspective, I’m pro-cities; density typically allows for lower CO2e emissions per sq km and per capita. From a social perspective, I’m pro-sturdy infrastructure; I almost died on a fairly suspicious Laotian bridge a few months ago. In all, I’m long $CMNT.

Concrete solutions are being developed to decarbonize this industry. I’m hopeful for a future in which my tax dollars are put toward filling potholes, ideally with a fine ratio of pulverized fuel ash, rubble of old buildings, injected CO2, aggregates, and water.

The recipe for cement varies by manufacturer. Different projects demand different combinations to produce the ideal concrete. For example, a change in relative humidity will cause movement. The steel within many concrete structures corrodes faster or slower depending on what the concrete is made of. Depending on the concrete quality, these impacts will be more drastic and occur faster.

The cost breakdown can be more accurately modelled by:

Y = - 2351,577 + 1,386 X1 + 0,856 X2 + 0,656 X3 + 279,253 X5 + 3,041 X6 + 2,576 X8

Y = Production Cost (Rp./m3)

X1 = Cement Usage (kg/m3)

X2 = Rubble Stone Usage (m3/m3 concrete)

X3 = Sand Usage (m3/m3 concrete)

X5 = Additive Usage (litre/m3)

X6 = Tool Period (year)

X8 = Time of Equipment Operation (hours/month)

Carbonation involves the calcium-containing phases of cement–such as calcium silicate hydrates, calcium aluminate hydrates and portlandite (Ca(OH)2)–reacting with CO2 to produce calcium carbonate.

Certain technologies, such as CarbiCrete’s carbon curing, make use of waste materials while also incorporating other carbon-storing technologies. These are not mutually exclusive approaches.

Alicia keys is a visionary